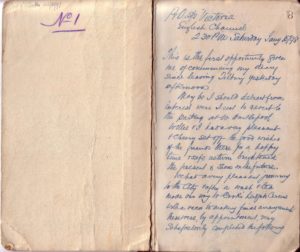

First Page of the Journals

I saw the journals for the first time 30 years ago. I was 16 years old and visiting my grandfather’s cousin who lived in the English countryside. William Whitehead was her grandfather, and the journals had been passed down to her from her father. They were nestled in a bottom drawer of the guest bedroom dresser, loosely bound up in brown paper and string. They looked very old and mysterious. She pointed them out to me without opening them, and told me that my great-great grandfather had traveled the world for an entire year and that these were the journals he kept. At that time, I couldn’t even begin to imagine what was in them, but I have been in love with history my entire life and knew I couldn’t wait to read them. She promised that one day they would belong to me.

I had started a correspondence with my cousin after learning of her existence only a few years earlier while completing a family tree project in the 8th grade. I asked my grandfather about our ancestry and he produced a worn, yellowed paper from his wallet with a handwritten address on it. Our family was originally from England, he told me, and that was his cousin’s address. He hadn’t been in touch with her for many, many years but he suggested I write. I did, and over the years I visited her several times.

Sadly, my cousin passed away in 1993 but– true to her word – she left the journals to me. They arrived in a box at our home on a cold winter morning and I got my first real look at them. There are 9 different notebooks, called manifold writers, and each one of them is different from the others. Some have colored marbled covers while others are simply black; most have 100 pages but Volumes 4 and 8 have only 50. William took a few with him at the beginning of the journey, and received several more from home, but he still needed to purchase others along the way. I imagine he never expected to write so much.

A manifold writer was a clever system for making copies of correspondence. Each thin, lined page of the notebook was attached at the inner edge to another heavier blank page underneath of it. William would slide a piece of carbon paper between the two, and a metal plate under the lower page for stiffness. Then, by pressing the pen firmly on the top page while writing, an impression of the letter could be made on the bottom page. Pens were often tipped with a stone called Agate to make the impression heavier. Once the page was filled, it could be torn out by the perforation and posted, while a carbon copy of the letter remained in the notebook. William wrote the Journal as a correspondence with his sister Barbara back home at West Hartlepool. The letters he mailed back have all been lost in the ensuing 120 years, but the carbon impressions remain in the pages of the manifold writers.

Once I had a chance to peruse the journals myself I found them rather difficult to read. The pages are small so the handwritten words are also small and packed tightly together, and William used a lot of abbreviations to save space. Moreover, the handwriting is often fuzzy and difficult to make out because it is only a carbon copy of the original. And finally, William used many words and allusions that may have been familiar to a Victorian living in England at the end of the 19th century, but to an American living at the end of the 20th, I found them hard to decipher. Because of all this, I never got much farther than just picking up the journals at random and scanning the datelines and locations of journal entries. For years I still had really no idea what was in them.

Then in 2003 my parents offered to transcribe the journals for me, so that we could finally read them properly. They did the hard work of reading through the journals word-by-word and line-by-line, and transcribing them into an electronic format. My mother would email me a few pages at a time and I compiled the whole text into one 400-page document. Then over the years I have added more than 750 explanatory footnotes to aid the reader in understanding the social and historical context of William’s journey. Finally, I hired a professional editor, Gavin Robinson of Different Hand Ltd., (www.differenthand.ltd.uk) to proofread the transcription and add a detailed index at the end.

Now, exactly 120 years after the start of William’s journey, I am prepared to make the journals available so that others can enjoy them as I have. The end of the 19th century was a fascinating period that was much like our own globalized world in many ways, with international trade, mass production and nearly instantaneous communication via telegram. And yet it also seems antiquated, with its horse-drawn carriages, sailing ships and corner grocers. By reading the journals, and immersing ourselves in William’s world for a time, I believe we can understand our own times just a little bit better.